Cosmic Distances from Lookout Observatory Photos

Dear Friends,

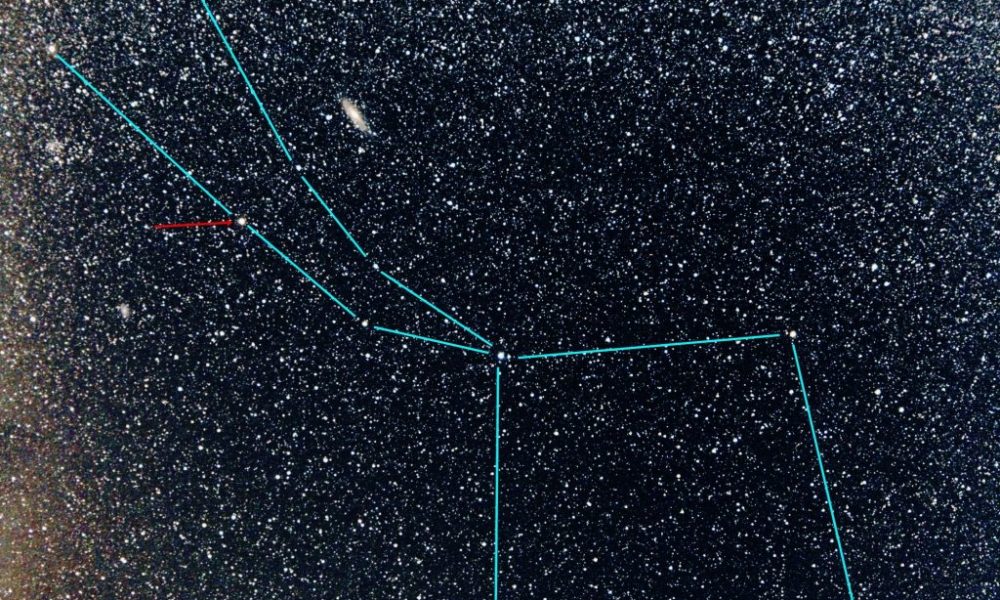

This time of year it is too cold to stay out all night photographing the skies, but it is a good time to reflect on the immensity of the universe. The first photo is of a fairly large region of the sky (about 35 degrees on each side) that includes stars in the constellations of Pegasus and Andromeda. The square marked with blue lines identifies the four stars known as The Great Square of Pegasus. The upper left star actually belongs to the constellation Andromeda, and the blue lines that angle up and to the left to make a narrow curved “V” connect many of the other brightest stars that make up the constellation Andromeda. The star with the red arrow pointing to it is Mirach, the second brightest star in Andromeda. To the upper right of Mirach is a corresponding star in the other leg of the “V,” and an equal distance beyond that is a bright oval patch, which is the Andromeda Galaxy known as M31.

M31 is the closest large, bright galaxy to our own Milky Way Galaxy. Galaxies tend to group in clusters, and there are approximately 50 galaxies that make up our so-called Local Group. Most of these are small, faint galaxies – so-called dwarf galaxies – and many are closer to us than M31. M33 is the name of the other relatively large, bright galaxy that is part of our local group of galaxies. It can be seen in this photo as a small fuzzy patch about the same distance from Mirach as M31, but in the opposite direction. If you enlarge the photo a lot, you can see that the outline of M33 is irregular, unlike the image of Mirach, a star, which is perfectly round. M31 and M33 are the farthest objects you can see with the naked eye. They are faintly visible in a dark sky, at the very limits of visibility. You normally can’t see them from within a city. You need dark suburban or country skies. This time of year just after it gets dark M31 is almost directly overhead in the sky.

All of the stars in this photo, whether bright like Mirach or faint like the thousands of tiny dots sprinkled in the background, are all within our Milky Way Galaxy. The star closest to our Sun is Alpha Centauri (not visible in this photo). It is about 4.3 light-years away. A light-year is the distance light travels in one year – about 5,900,000,000,000 miles. One of the brightest stars in the current photo is Mirach, and it is about 200 light years away. Just a short distance from Mirach in this photo is M31, but it only looks that way because they lie in the same general direction. Actually M31 is 10,000 times more distant than Mirach – about 2 million light years away.

The second photo was taken with a 420mm telephoto lens, and it is a close up view of M31, in the same orientation as the first photo with north up. Here M31 runs diagonally across the whole photo. If you enlarge it greatly, you can see a lot of detail in M31’s spiral arms and dust lanes, but every star in this photo is in our own Milky Way Galaxy, not part of M31. But notice the oval blob to the upper right from M31. This is M110, a satellite galaxy of M31. It is another one of our Local Group, and it is approximately the same distance from us as M31. Now look above M110 where the red arrow is pointing. If you enlarge the photo greatly, you can see that it is pointing to a very small, round blob near the limit of what can be seen in this photo. That blob is a very distant galaxy 1000 times farther away than M31! It doesn’t have a name other than the position that locates it on the celestial sphere. At its distance of about 2 thousand million light years it is one seventh of the way to the very end of the visible universe!

Another way to try to grasp these immense distances is to put them in a smaller scale. If we make the diameter of the Earth’s orbit around the sun 1/100th of an inch (about the size of a period on the page of a book), then the closest star would be about 26 feet away. The star Mirach in Andromeda would be a mile away, and M31 would be 10,000 miles away. The distant galaxy, that tiny smudge in the second photograph, would be one ninth of the way to the sun, and the edge of the visible universe would be almost to the sun. Of course, at this scale it would take about 650 of us laid head-to-toe to stretch across the smallest atom (a hydrogen atom)! Makes you feel kind of small, doesn’t it?

Happy New Year,

Carter Mehl,

(sometime) Resident Astronomer,

Lookout Observatory