A Lookout Observatory Bulletin: Our Galactic Neighbors

Dear Friends of Lookout Observatory,

First, a technical note. My trusty astrocamera, after 9 years of happy use, was beginning to get glitchy – sometimes it would stop working in the middle of a picture series, and I would have to restart the software program on the computer that runs the camera, or restart my whole computer, and then start over again. This was very frustrating, so the obvious solution was to buy a bigger, better and more expensive astrocamera. What I didn’t count on was that the old software wouldn’t run the new camera, and the old computer wouldn’t run the new software I had to buy. This meant getting a new computer and spending a lot of time learning how to use the new software in a way that worked well for the new camera. This is pretty complicated stuff for my aging brain, so it has been many months before I could start taking decent pictures again.

To complicate things further, all the forest fires raging in northern California made so much smoke that getting good photos from Lookout Observatory has been impractical this whole summer. So I accepted an invitation from my friend Dr. Fritz Kleinhans to meet him near Silver City, New Mexico, where we had dark skies at about 4800 feet elevation. I apologize for such a long delay in getting any new pictures out, but now here we go with some of the first images from my new camera!

Galaxies, like people, like to hang out in groups. We of course live in the Milky Way Galaxy, and the galaxies nearby (within about 5 million light years) are called the Local Group. The 3 largest galaxies in the group – all spiral galaxies — are the Andromeda Galaxy (also known as M31), the Milky Way, and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33). All the others in the Local Group are considerably smaller; many are spheroidal dwarf galaxies. There may be as many as 100 galaxies altogether. Nearby but very faint galaxies keep being discovered as professional telescopes get ever more powerful. These Local Group galaxies are not randomly distributed. They occur in two clumps, one surrounding our Milky Way, and one surrounding the Andromeda Galaxy. Most of these other galaxies are satellites of – gravitationally bound to – either the Milky Way or the Andromeda Galaxy.

The first picture is of the largest member of our Local Group, the Andromeda Galaxy, about 220,000 light years across and containing about one trillion stars. You can see the tightly wound spiral arms filled with young, hot blue stars surrounding the yellowish core of older stars. In addition you can see two satellite galaxies. M110 is the oval patch above and to the right of center. And M32 looks like the brightest star directly below the center, but it is actually a very compact elliptical galaxy. Because the Andromeda Galaxy is so close to us – only about 2.5 million light years away – it looks large and bright (for a galaxy). It can be seen with the naked eye from a dark location. North is up in this picture, and it covers 2 degrees by 3 degrees of the sky, so five full moons could fit across the length of the galaxy as photographed here. The 3 additional pictures that follow are enlarged to 2x this scale, so they all cover 1.2 degrees by 1.5 degrees. Please zoom in on all images to see more detail.

The Milky Way galaxy is about ¾ the diameter of the Andromeda Galaxy , about 1/2 the mass, and contains about 1/3 the number of stars. Since we live inside it, it is hard to get a picture of it. The third large galaxy in our Local Group, the Triangulum Galaxy, is about 1/4 the diameter of the Andromeda Galaxy, about 1/30 the mass, and contains about 1/20 the number of stars. So while our galaxy is just slightly smaller than the Andromeda, the Triangulum is much smaller. It is closer to the Andromeda Galaxy than it is to us, and it is probably a satellite of that galaxy. It is shown as the second image. The many pink areas in the blue spiral arms indicate lots of hydrogen gas where new star formation is taking place.

My wife Anitra is my reality check that not everyone has a deep interest in astronomical minutia. Her comment on the next two pictures was “they are just little blobs,” so if you react the same way, you are normal. If however, you have a deeper interest in astronomy, read on.

The third picture is of one of the many satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. It is just over ¼ million light years away – very close for a galaxy – but because it is a very different kind of galaxy, vastly smaller than the Andromeda Galaxy, it is also much fainter. In fact, it is so faint that it was not discovered until 1937, and it is difficult to see even in a large amateur telescope from a dark location. It is visible here because its faint light was accumulated over 1 and ½ hours. It is known as the Sculptor Dwarf galaxy, and it is that dim round patch of faint white and bluish stars in the center. It is remarkable that we can see some of the individual stars in this galaxy. All the brighter stars in this photo are foreground stars in our Milky Way, roughly1000 times closer than the Sculptor Dwarf. This galaxy came into existence before our own Milky Way, and its total mass is less than 1/1000 of 1% of the Milky Way’s. As boring as these objects might be, they are numerous. There are probably 10 to 20 times as many dwarf galaxies in the universe as there are large, beautiful galaxies like Andromeda, the Milky Way and the Triangulum Galaxy.

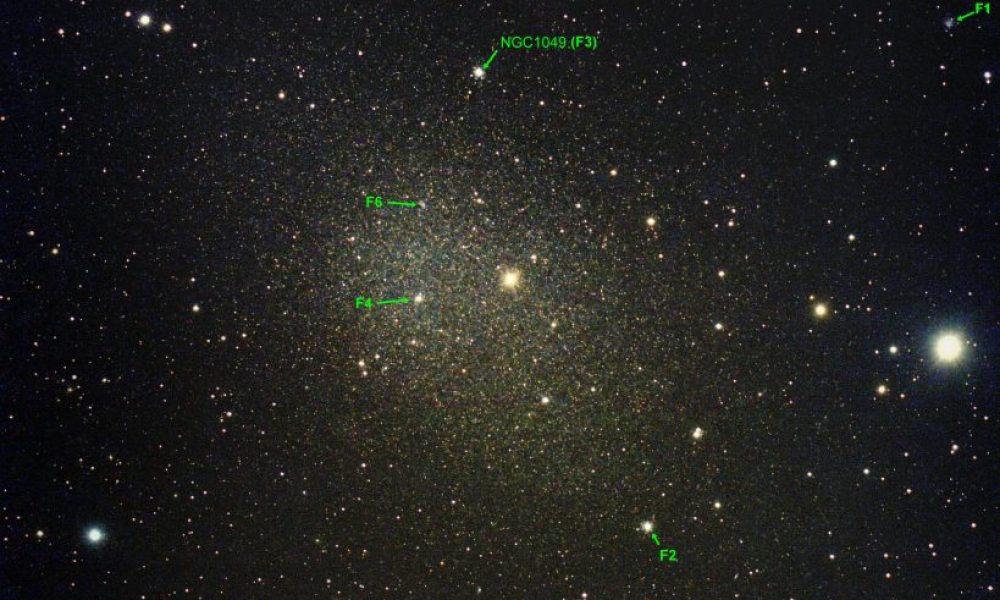

The fourth picture is of another small satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, the Fornax Dwarf galaxy. At least 10 times as massive as the Sculptor Dwarf, it was discovered just a year later, and it is about 1 and 1/2 times as far away and somewhat brighter. The tiny objects labeled F1 through F5 in this picture are globular clusters associated with this galaxy, and their presence makes this galaxy very interesting to astronomers.

Most large galaxies have densely packed spherical clusters of tens or hundreds of thousands of stars – known as globular clusters – surrounding them in a kind of halo. The Milky Way has at least 150 and Andromeda has as many as 500. Most dwarf galaxies have none or only a few. The Fornax Dwarf has the 5 labeled here. The individual stars in them are too dim and tightly packed to be seen in this image, so they just look like very small bright blobs. Interestingly, the one labeled NGC1049(F3) was discovered in the 19th century, about 100 years before the galaxy itself was noticed (because it is so faint). This globular cluster was number 1049 in the New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (abbreviated as NGC), published in 1888. Professional astronomers have used these globular clusters to help determine that this galaxy (and most dwarf galaxies) contain large amounts of dark matter, far greater than the amount of matter in the stars themselves.

The little blur labeled F6 in the Fornax Dwarf image was first thought to be a sixth globular cluster (hence, its similar label), but more recently it has been determined not to be one. Exactly what it is is still not completely clear, but it has been suggested that it might be a very compact group of very distant galaxies shining through the Fornax Dwarf galaxy, which in turn is shining through the foreground stars of our own Milky Way – just another of the many wonders of outer space.

Keep looking up,

Carter, (sometime) Resident Astronomer,

Lookout Observatory

P.S. Technical information was assembled from recent Sky & Telescope Magazine articles, Wikipedia, and online articles by professional astronomers. Details change frequently as new discoveries are made.