Giant Hydrogen Bubbles in the Milky Way

Dear Friend of Lookout Observatory,

The arms of spiral galaxies like the Milky Way tend to be filled with many young, hot blue stars and giant hydrogen gas bubbles or nebulae. Hydrogen, the simplest and most abundant element in the universe, consists of a single proton with a single electron. Hot blue stars emitting high energy ultraviolet light in the midst of clouds of hydrogen strip away the electrons, leaving ionized hydrogen (single protons without the accompanying electron) and causing them to radiate a single wavelength of red light (called H-alpha). Large nebulae of ionized hydrogen gas are known as HII (pronounced H-two) regions, and they are common in the arms of spiral galaxies. Today’s pictures are of a group of large nebulae of ionized hydrogen in our own galaxy, glowing with the red light of H-alpha.

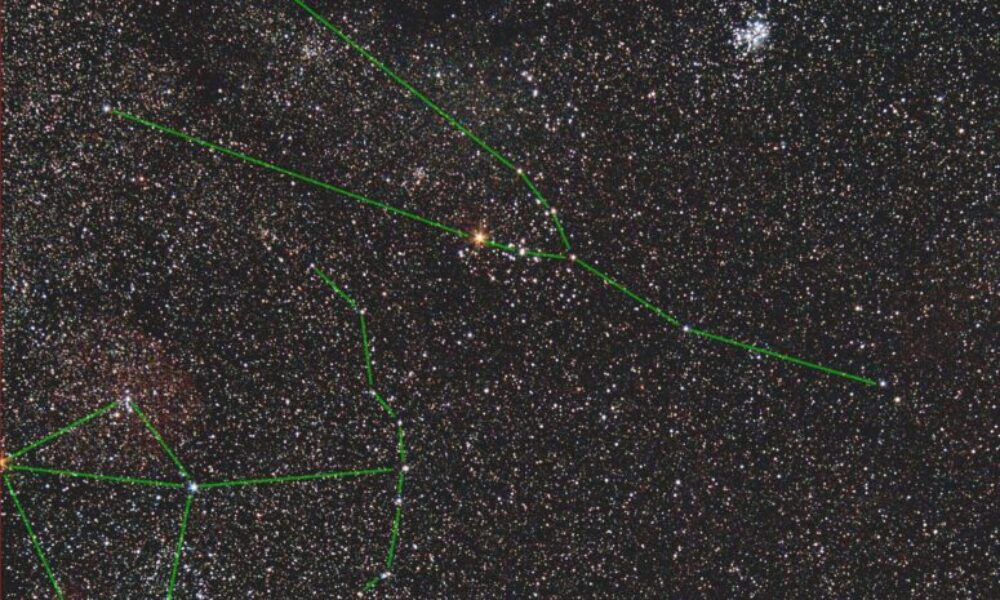

The first picture shows a large area of the winter sky, with Orion at the lower left, the constellation Taurus in the center (with it’s brightest star, the red giant Aldebaran in the center of the picture, the Pleiades cluster above and to the right, and the southern part of the constellation Auriga in the upper left corner. Green lines are added to help you follow the brighter stars that make up the constellation star patterns. The bright blue rectangle outlines the 5½° x 7° area of Auriga that is shown in the next picture.

Most of the second picture is filled by a huge hydrogen bubble known as Sh2-230, but despite this being an almost 4 and ½ hour time-exposure, much of this cloud is invisible or very faint. The faint reddish-gray swirls, splotches and streaks (as distinguished from the slightly darker bluish-gray background) are all part of this giant hydrogen bubble about 900 light years in diameter. Brighter, denser parts of this hydrogen nebula are given separate names – the Spider Nebula and the Tadpole Nebula, for example. The largest bright nebula (at the right), named the Flaming Star Nebula, is not part of the giant Sh2-230 nebula. It is only about 1/7 the distance to Sh2-230, and it looks so large and bright because it is so close. Most of the other red hydrogen nebulae in this photo are star-forming regions and have recently formed clusters of stars embedded in them. In addition, in this picture are 3 identified open star clusters (M36, M38 and NGC 1907), each with a few dozen to a few hundred stars, and all lie in front of Sh2-230, being less that half as far away from us.

Close up photos of the Tadpole Nebula and the Flaming star Nebula are the third and fourth pictures, and those of you who enjoy the pictures but tire of technical details should just look at them and ignore the very wordy explanations that I’m going to continue with for those with deep astronomical interest. All except the first picture of the winter sky were taken through a narrowband filter (to screen out heavy light pollution), so red color is emphasized and the colors aren’t quite true. Nevertheless, please enjoy the cosmic beauty!

Click on any image to get a closer look

For Hard Core Folks

Let me start with a note about naming and then go through more detail about objects in the second picture. Stewart Sharpless, an astronomer with the US Naval Observatory, in 1959 published his second catalog of 313 nebulae, mostly ionized hydrogen (HII) regions. So Sh2-230 is number 230 in his second catalog. Many of the brighter nebulae in his catalog have multiple names because they were already listed in other, earlier catalogs. Charles Messier in the eighteenth century published several editions of a catalog of fuzzy objects, so the brighter deep sky objects (star clusters, nebulae and galaxies) are identified as M with a number from his catalog after it. The New General Catalog of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars ( abbreviated NGC) listing almost 8000 such objects was published in 1888, and by two decades later more than 5000 additional objects were given numbers in supplemental Index Catalogs (abbreviated IC). So for example, the Tadpole Nebula is known as IC410, but also as Sh2-236.

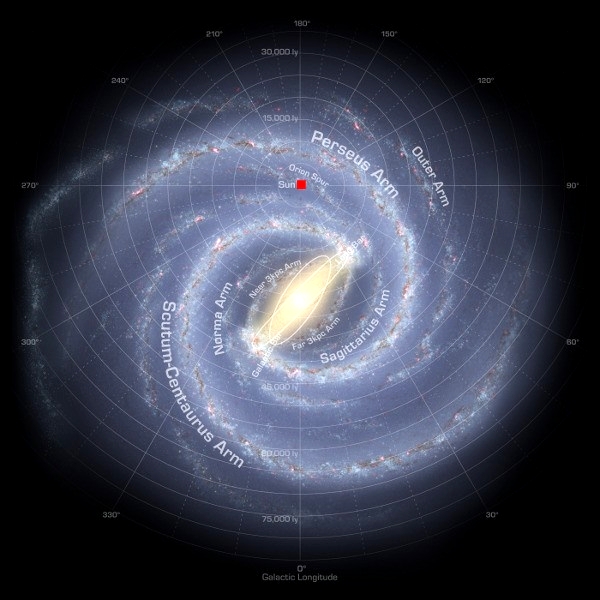

All the objects in the second picture are in the winter Milky Way, that part of our galaxy looking away from the center. Below is a drawn map of our Milky Way galaxy as seen (imagined) from above, looking down onto the plane of our spiral arms. The location of the Sun, about halfway from the center to the edge, is shown by the bight red dot. This map was made in 2008 by Robert Hurt, an astronomer at the Spitzer Science Center, and revisions are being proposed as more information is learned.

Note that the center of our galaxy instead of being round is stretched out into a bar, and the spiral arms start from the ends of that bar. This is known as a barred spiral galaxy. The earth revolves around the sun in approximately the same plane as the plane of the galaxy. In the (northern hemisphere) summer the earth is closer to the center of the galaxy than the sun is, so at night when we see the summer Milky Way, we are looking toward the center (looking down on the map). In the winter the earth is on the opposite side of the sun, farther away from the galaxy center, and when we look out at night, we are looking up on the map, away from the center. The winter Milky Way looks dimmer in the sky because we are looking at only about ¼ of our galaxy rather than in the summer when we are looking at ¾ of it, including the densest center part. Many of the objects that I photographed this winter in the second picture, including the giant nebula Sh2-230, are about 10,000 light years away from us in the Perseus arm of our galaxy. (Note the concentric circles on the map going out from the sun’s position are 5000 light years apart, so going up anywhere from about 6,000 to 10,000 light years from the sun on the map puts us in the Perseus arm.)

Starting at the left in the second picture, we have the small, bright red splash of Sh2-235. It and the tiny red circle named Sh2-233 just to the right of it plus several other HII regions not shown here are all part another huge hydrogen cloud – separate from Sh2-230 — in the Perseus arm. New stars are forming in these HII regions. Moving further to the right we come to a small red spot labeled Sh2-237 (also known as NGC 1931 and the Fly Nebula because it is small and close to the Spider Nebula). Small is relative; it is over 10 light years in diameter! This and the neighboring Spider Nebula both have young star clusters recently born out of the condensed hydrogen gas. The Tadpole Nebula, like the Spider and the Fly, is a more concentrated region of the vast Sh2-230 hydrogen bubble. The star cluster embedded in its center (with it’s own name of NGC 1893) contains about 4600 stars born there about 4 million years ago, very young in cosmic time.

If you look at the third picture, which was taken with a larger telescope than the second picture, you will see a larger, more detailed view of the Tadpole Nebula. Just above and slightly left of the central star cluster are two little red tadpoles of denser gas facing the cluster. This is how the nebula got its name. Their shape is being sculpted by the stellar winds (radiation pressure and particles) from the hot blue cluster stars. These two “little” guys are each about 10 light years long. The bluish cast to parts of the nebula is caused by blue light from the cluster stars being reflected off of dust particles, which are commonly scattered throughout such HII nebulae.

And finally, the fourth picture is of the Flaming Star Nebula taken with a larger telescope. As I mentioned before, this nebula is much closer than the Perseus arm, only about 1500 light years distant, so it is in the same arm as the sun, the Orion Spur. On the map it would be only a little bit outside of the red dot, since the dot itself is has a radius of about 1000 light years. Unlike the other nebulae that have embedded clusters of high energy stars that are causing the gas to glow, this hydrogen nebula is energized by strong ultraviolet radiation from the single brightest star in the nebula (a bit above the center of the picture). It goes by the name AE Aurigae. This star was not born here, but rather is an interloper, having been ejected a few million years ago from the Orion Nebula region, and is now only passing through this cloud of hydrogen, causing it to temporarily glow brightly. And this ends our tour of the sky in a small region of the constellation Auriga.

Infomation came from various online resources, mostly Wikipedia, NASA, and especially Kevin Jardine’s Galaxy Map at galaxymap.org.

Keep looking up,

Carter, (sometime) Resident Astronomer

Lookout Observatory